If you’re one of the 1.2 million Australians with communication disability or among the 44% of Australian adults with low literacy, you may soon find helpful, automated communication assistance online.

The chat bot ChatGPT – based on GTP3, a large language model – is a disruptive technology designed to “provide human-like responses” to user input. It is a form of artificial intelligence (AI), boosted by machine learning, is used by more than one million people and is impressing educators.

It responds to the user’s questions and commands, and can draw upon its billions of words to process and generate text, appearing informative and knowledgeable.

Described somewhat poetically as producing “fluent bullshit”, its unchecked outputs may be plausible enough to score a pass mark on assignments and tests, while bypassing plagiarism detection software.

If it becomes accessible for everyone, AI of this type could do more than disrupt exams. It could help people with communication disability and others who struggle with text, and could also significantly enhance rate of communication. People using speech generating devices are often limited to laboriously entering a mere 10 words per minute with word prediction only increasing that to 12-18 words per minute.

Communication disability can leave you lost for words – and excluded

There are many types of communication disability impacting a person’s ability to speak, understand, or write.

Impairments of speech, language and social communication are associated with a wide range of conditions including cerebral palsy, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and motor neurone disease. Communication disabilities can impact the clarity of your speech and what you can say, your ability to understand others or express yourself, and your skills in reading and writing.

A communication disability can mean you need to economise on what you say, as each word takes more effort and time to produce or write. If you have limited literacy, you’ll need text simplified to make sense of it. You’re also more likely to encounter more barriers to completing training, getting a job, forming relationships, managing your own health and life decisions, and participating in social networks.

How technology like ChatGPT could help

AI like ChatGPT can help pull information together in a neat text, and it can turn written text into a summary for readers with low literacy.

We already know that AI assistants like “Alexa” and “Siri” can help people with intellectual disability and speech impairments to communicate and speech-recognition software is improving.

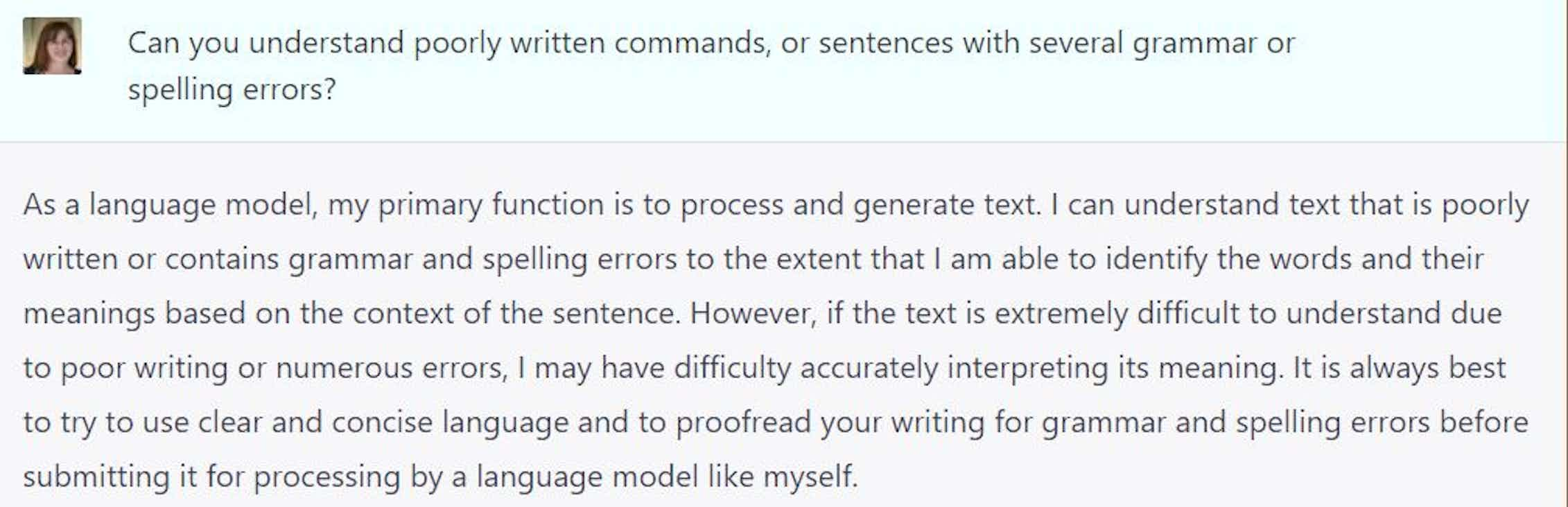

But ChatGPT looks like it will be more inclusive of diversity by being able to understand poorly written commands, or sentences with several grammar or spelling errors. It can reportedly “read” poorly structured input, re-write and improve imperfect writing, and simplify complex texts into simpler summaries for early-stage readers. ChatGPT could be considered an “assistive technology” if it assists people with communication disability to get their message across more efficiently or effectively.

Read more: The dawn of AI has come, and its implications for education couldn't be more significant

A user perspective

As a qualified lawyer and a person with cerebral palsy and no speech, co-author Fiona Given relies on assistive communication technologies, including augmentative and alternative communication speech-generating devices. Fiona says:

[…] each word and message that I compose takes me substantially more time and effort than a person who speaks. So I economise on that, and my written messages using current assistive technologies are often short and to the point. This can cause many problems, as I may be perceived as curt, if not rude, and I’m also not fully explaining what I mean.

Having tested the system, Fiona says ChatGPT could be particularly useful in adding the polite parts of emails and letters.

It can save me time and effort whilst maintaining my professionalism. One day, AI like ChatGPT may be installed into my speech-generating device. Yes, it raises questions of authorship and brings in doubt over who did the writing. That’s the case also with word prediction software – who thought of the word first? I see it as a type of co-authorship, and people like me will still need to be able to read and check it reflects what they want to say and edit and authorise the output accordingly.

AI technologies like ChatGPT may help people with communication disability to:

- expand on short sentences, saving time and effort

- draft or improve texts for emails, instructions, or assignments

- suggest scripts to practice or rehearse what to say in social situations

- model how to be “more polite” or “more direct” in written communication

- practice conversations, including asking and answering questions

- correct errors in texts produced for a range of purposes

- write a complaint letter, including nuance and outcomes of not taking action

- help with making that first approach to a person socially.

Future AI must be inclusive and accessible

Given its potential for text-based assistance, it is important to know if people with communication disability will be able to access chatbots like ChatGPT.

We don’t know how many of the one million users testing the ChatGPT system now have problems with literacy, written expression, or spelling. But so far it looks like a game changer to help people produce texts with little or less effort.

The experiences of people with communication disability in using AI like ChatGPT are vital in the future co-design of assistive technologies. We need to know more about their views on acceptability, usability, and authenticity of the messages produced. With a screen reader, the ChatGPT output could become the user’s “voice”. So being able to check, edit, and confirm or reject AI writing is vital. Any incremental improvements to chat bots, that take into account what helps and hinders access and inclusion, are important if people with communication disability are going to benefit from advancements in AI.

Bronwyn Hemsley has received research grant funding from the Australian Research Council and the National Disability Insurance Scheme Quality & Safeguards Commission for work unrelated to this article.

Emma Power receives funding from National Health and Medical Research Council and the Medical Research Future Fund. She is a member of Speech Pathology Australia.

Fiona Given does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.