Research shows that in the past 50 years, social class mobility – how a person’s occupation, social class or income compares with that of their parents – has either increased or stayed static in the UK.

But social mobility chances vary substantially depending on where you grow up and move to later in life, as our research has shown to be the case in the England and Wales.

The UK government has often relied on education policy to try to improve these geographic inequalities. This is often based on the fact that those with better education have improved life outcomes, including occupation, salary and health.

There’s also a looser, intuitive sense that education simply must be the right tool. What better way to counter social stagnation than to improve children’s education?

Our research has examined the effect on social mobility of one of the biggest education policy shifts of the 20th century in England: the move away from the grammar school system towards comprehensive schools.

We found little evidence to support the idea that either selective or comprehensive schooling improved overall social mobility outcomes. This shows that it cannot be assumed that education policy will boost social mobility.

The grammar system

Between 1945 and the 1970s, England and Wales had a selective schooling system where primary school pupils were allocated to an academically focused grammar school if they passed an ability test taken at the age of ten or 11. If they did not pass they would instead attend a secondary modern school or technical college.

Grammar schools were intended to pick out the best and brightest at an early age, regardless of their social background. But they have also been criticised for reinforcing social division, because wealth appears to be a strong driver of grammar school attendance.

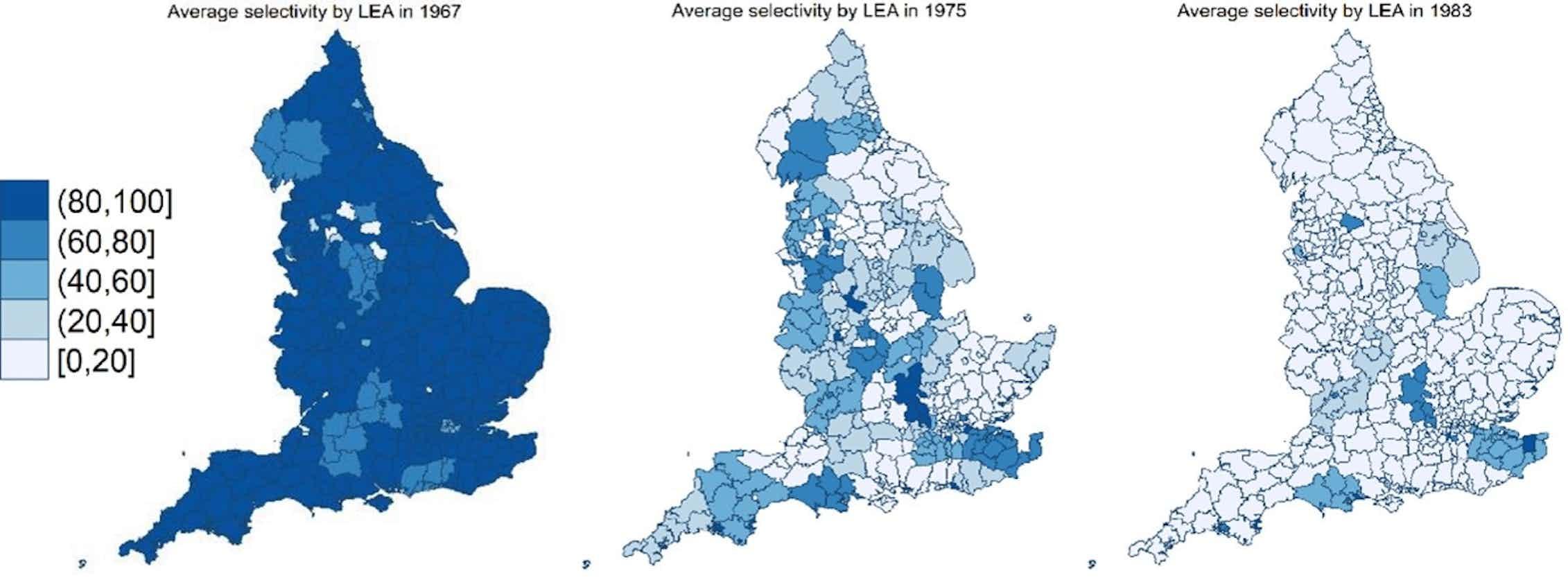

This system was eventually phased out in favour of mixed-ability education in comprehensive schools, and this shift occurred differently in different areas. By the early 1980s only a few local authorities maintained some form of selectivity. Today, 163 grammar schools remain.

Average school selectivity by local education authority over time

We looked at the social class mobility of a representative sample of more than 90,000 people over five decades. We found that the abolition of so many grammar schools in the 1960s and 1970s did little to change overall social mobility levels. Social mobility levels did rise during this period, but our analysis found no link to the rapidly changing nature of the school system.

Other factors at play

When comparing education and earning outcomes of young people educated in grammar schools to those educated in comprehensive schools, analysis has found some better outcomes for those attending grammar schools. But other factors, such as parental education, family income and the area where the family lives, are difficult to account for and may have had a role in these better outcomes.

Because our study looked at variation in school system both across areas and over time, we were able to use statistical techniques which can account for such factors and the effects of broader societal trends over time. This provides more credible results.

For the purpose of education policy, the key question should be about how to design the broader school system for the benefit of all pupils – rather than a narrow focus on outcomes for those who do gain a place at a grammar school. The outcomes of those who missed out on a grammar school place are important too. Our research addresses this by studying the effects of the schooling system as a whole.

Past research by one of us (Franz Buscha) looked at a similarly important change in education – the raising of the school leaving age in 1972 from 15 to 16. This changed also showed little statistical effect on social mobility. This means that taken together, the two most powerful educational interventions in the 20th century did not result in significant changes in social mobility.

This raises questions about the broader societal impact of education policy more generally. We are not saying that education is not worth investing in, or has no prospects to improve life outcomes. But for these specific policies, we might have expected large effects – and did not find them.

Designing effective education policy is difficult, but important. Education affects our social, emotional and cognitive skills, as well as our earnings and employment. But role of education in driving social mobility is complex, and education cannot be focused on in isolation – as factors such as early life circumstances and socioeconomic status are also crucial in shaping life outcomes.

Franz Buscha received funding from the ESRC via grant ES/R00627X/1. The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study is gratefully acknowledged, as is the assistance provided by staff of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS). CeLSIUS is supported by the ESRC under project ES/V003488/1.

Emma Gorman received funding from the ESRC via grant ES/R00627X/1. The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study is gratefully acknowledged, as is the assistance provided by staff of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS). CeLSIUS is supported by the ESRC under project ES/V003488/1.