“Suppose there were a writing of the non-written. Someday it will come. A brief writing, without grammar, just words. A writing of words without the support of grammar. Wayward. Written here. And immediately abandoned.”

—Marguerite Duras

*

There is no paradise in Marguerite Duras. Not even a literary paradise in which words might find an eternal felicity. She has not concealed her nostalgia for such a thing. But although not Edenic, her writing is at least redemptive. Life and literary invention accommodate themselves miraculously in the enthusiasm of a nascent inspiration: brief, intense moments of grace, of inexpressible joys; a door open onto infinity, even onto immortality.

No More brings Marguerite Duras into confrontation with the ultimately alien nature of death. Without vanishing, the perspective constantly deviates. The book gives an impression of breathlessness, of a visionary spirit exhausted from vertigo, overwhelmed by a melancholy that diminishes the murmur of words.

No More echoes a long appeal, ardent and despairing, stubborn, futile. The world crumbles, the alarming signs of the end are written everywhere in capital letters.

No More is not a codicil, but a singular testament alternating meditation and whispered confidences, praise and rage, hope and regret.

No More, from dedication to farewell, remains a book of love offered to the man whose name appears at the head of the dedication: Yann, the book’s other voice.

Life and literary invention accommodate themselves miraculously in the enthusiasm of a nascent inspiration.Thereby, of course, No More seems to belie this sentence from Écrire (1993): “No one has ever written in two voices,” since it presents itself in part as a dialogue in which the author has her—predominant—place, but in which Yann is not separate from the tragedy.

A book in two voices, then? A book which will rouse the curiosity of certain readers? No doubt some will wonder how these scattered fragments have been gathered together, who has bestowed the final touch upon the work. Of course… No More might be called The Book of Questions.

Yet we must attempt to separate the grain from the chaff. At the blind point where words encounter things, far from secondary interrogations, other interrogations appear—primordial ones. Erotic obsession, suffering, the line of fracture between two states of being, lucidity, bewilderment, a now impossible creation, the impossibility of writing, the sentiment of never more—this is the labyrinth in which language helplessly tries to beguile death.

A language which insists on being uttered aloud because it exposes at every line the untranslatable nature of life. A violent or helpless language whose secrets must be wrested from it. A language which is inscribed in the ongoing structure of a whole and which does not deter it.

For No More exposes old paths. We may approach it outside of its apparent limits. Madness occasionally murmurs here, a conversation with the invisible. The past is remembered. Freed from reassuring chronology, interrupted by silences, it gradually diminishes. By certain expressions we can measure the depth of an imminent and total dispossession of the self which is nonetheless opposed, as if in a kind of exorcism, by a lacerating hymn to life.

How to proceed here—by what itinerary? If it is true that a good reading, according to Marguerite Duras, should start from the “source,” following it to the ultimate reservoir of its waters, in order to deliver certain truths, not of the surface but of the depths, permanent truths, no doubt we shall find a necessary premise in the importance of the role played by Yann:

You will have been mine to your very soul.

When Yann comes to Marguerite Duras at Trouville on the Channel coast, in July 1980, though he knows her slightly, though they have exchanged letters, the encounter is now decisive. Fascinated by each other—he by the woman who has written The Ravishing of Lol Stein (1964), India Song (1973); she by the intelligence and youth of this student of philosophy, by his admiration for her—everything now offers an opportunity to recover the living roots of the erotic passion she has unceasingly celebrated in her life and in her books.

That abominably stable summer, she seems abandoned by Venus, who had so often rewarded her. Many recent works proclaim her abandonment, which nonetheless finds no ally in la délectation morose. Work now resumes, for the absent hour, the task of love. Always richly confident in life, Marguerite Duras transforms the void into expectation. Rebellious, she sends up her distress signals; as in Le Navire Night (1979): “And then nothing more happened. Nothing more. Nothing. Except always, everywhere, those cries, that same lack of love.”

And in The Truck (1977): “She might have said straight off: there is no story outside of love.” Or again, in Les Mains Négatives (1979): “I summon the one who will answer me. I want to love you I love you.” Belatedly, Writing explains the suffering of those years and the help afforded by work: “To find yourself in a hole, at the bottom of a hole, in a virtually total solitude and to discover that only writing will save you.”

The summer of 1980 inaugurates a fruitful renewal and institutes an erotic future of which she had reported, in 1977, to her friend Michèle Manceaux: “When one has heard the body—I should say desire, whatever is imperious in oneself…if one has not known the passion which takes this form, physical passion, one knows nothing.”

Three years later, Yann knocks at her door while she remains silent, moved: “ten years ago I was living in a very strict, almost cloisteral solitude.” At grips with a new ardor, wrenched from her soliloquies, she turns from isolation to ecstasy. No More reflects that fire which prowls on the confines of words and assures the text’s irreplaceable particularity.

Throughout, memories glisten, the determination to withstand disappointments or failures provokes love-cries with complex echoes. And these cries, as much as the desperate fever to keep death at a distance, as much as the despairing shame of being unable to hold onto life, inscribe the book’s lines of force. Lines of flight as well, for erotic discourse involves an endless wandering in the forest of signs, disperses in enigmatic impressions, and is lost in the depths of consciousness.

Her body a captive of every one of her senses, extenuated by reason of her weakness and illness, caught in the trap of her eyes fixed on the lover of the night, frequently clairvoyant about herself, Marguerite Duras manages to produce the words which release her and commemorate the transports of this passionate adventure. Whereby we recognize her readily enough. Nothing deletes the fundamental power which she confers upon love: “The word love exists,” she maintains on June 28, 1995.

Nonetheless, we observe on the one hand that if this word persists down to the last lines of No More, it yields to the death which haunts this universe and which is ever more chaotic, ratified, abysmal. As in her books? Yes, except that the stake here is of a different nature. Two antithetical absolutes do battle in an unequal combat won in advance, lost in advance. Forever.

Although not Edenic, her writing is at least redemptive.On the other hand, following her natural tendency, if Marguerite Duras clearly designates Yann as the object of her love, she does not avoid certain intervals which frustrate the biographical, projecting it into the vagueness of a tutelary dream. Incontestably, desire for Yann is expressed in terms of the woman who experiences it. Homage rendered to its charm is not lacking:

You are becoming beautiful.

I look at you.

Desire mobilizes attention, sensitive to this or that aspect of the lover, to his hands which advance with the hill, to his blondness, to his strength. Sometimes the fear of a distraction is apparent: “I have not said enough about his person, his soul, his feet, his hands, his laughter.” We shall not be surprised to find such terms indissociably yoked together. Soul and hands, feet and laughter, all are of equal worth for Marguerite Duras. Hence the effusion, of a carnal order, which she can whisper to herself, in a delicate incantation, a tender lullaby:

I wait for you the way I wait for someone who will destroy this failed grace, gentle and still warm.

Given to you, wholly, with my whole body, this grace.

Or, without any evasion, quite directly:

Give me your mouth.

Come quick so we can go quicker.

Quick.

No more.

Quick.

Such subjugation, which is also a feature of possessiveness with regard to Yann, does not escape thought’s slippage toward ill-defined, unidentifiable characters, a dream procession, other faces of love.

I want to talk about someone.

About a man of twenty-five

at the most.

He is a beautiful man…

Or:

The name: I don’t know.

It is not important.

To be together as with a

lover.

I would have liked that to happen to me.

With No More, Marguerite Duras has entered a region unknown to her where all points of reference are turned upside down. On July 24, 1995, she feels herself to be frozen by madness. On December 29, her whole body is in flames. Nonetheless, the love sought for, hoped for, found at last, lost, regained, has never broken out of the circle in which it has remained since her first affair. Sometimes it appears to escape this circle in order to focus on a lover, on someone. But the escape does not seem indispensable, for love does not manifest itself only by the impulse toward the other. As we read in Emily L. (1987), love closes over itself, mutates into a way of being:

I wanted to tell you what I believe. Which is that you must always keep for yourself, yes, that is the word for it, a place, a sort of personal place, that’s right, to be alone there and to love. To love you don’t know what, nor whom nor how, nor for how long. To love, and now suddenly all the words are coming back to me…to keep inside yourself the place to await such a love, perhaps a love without a person as yet, but for that and that alone, for love.

If the lover erases contingency, if he remains a chosen intermediary by which the world recovers its luster, he is not, for all that, the subject of a cult offered to him alone. He may serve as the excuse for an apology of desire for desire’s sake, having no hold over the woman who loves him. She will never release her prey for some illusion—that is, will never surrender her autonomy, for the sake of fidelity to the lover, however seductive. On occasion the lover may be alarmed or irritated:

What you wanted was this contradiction: to be in a love which fulfilled you and to summon another love to the rescue.

To which the retort is made, still in Emily L: “Not entirely…neither to summon another love nor even to hope for such a thing. Only to write within it, to write out of it.”

To write, to love. Both lead to disorders and to delights, both are experienced in the same defiance of knowledge reduced to despair, both come to terms with the most opaque realms of the mind where nothing is mastered.

__________________________________

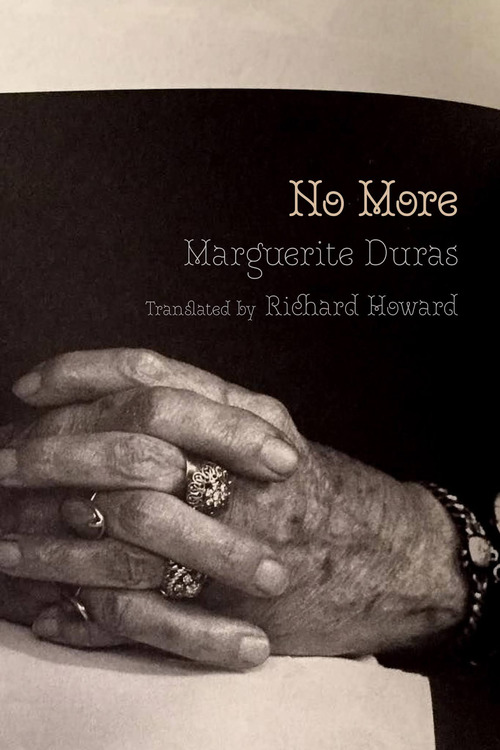

From the afterword of No More by Marguerite Duras, translated by Richard Howard. Copyright © 2023. Now available in a bilingual paperback edition from Seven Stories Press.