It’s the most unlikely things that get you: how he pours salt into his hand before sprinkling it pinch by pinch onto his asparagus; the way he looks up over his glasses with eyebrows arched and magnified eyes startled, perhaps, that the world is in fact right-side-up; the green button-down shirt with the cuffs rolled to the elbows and the unflattering jeans and the thick white socks and the white rubber gardening shoes, none of which have been changed in the three days since you started to notice him at all and maybe longer; and the way he catches you watching him pinch salt onto his asparagus and blinks giant eyes at you with purpose, with resolve, because you did something like this two days ago when you noticed him watching you deliver your lunch tray to the dish cart, and he’s caught on, and this is flirting, and he’s going to give it a whirl. Not to mention, of course, certain pertinent details of your own personal life, namely, that you are, as of a year ago and admittedly with some reservation (hadn’t there been some reservation?) — yes, in hindsight it seems like a grave mistake but at the time, how had you felt at the time? — married.

He lingers at the lunchroom table with no food or drink in front of him, and you realize of course that you’ve communicated your interest a little too clearly and he’s lingering just for you, and after he’s finally given up and left, your fellow teachers at the table say with revulsion (and with some affection, too) that he seems so “out of phase.” What do you do when this ticklish absurdity masquerades as persistent, budding joy? What do you do?

You wander casually into his photography studio as you and the other teachers have been invited to do, to come and enjoy the camera obscura he’s made of the room, lens-boxes in every boarded-up window and bed-sheet partitions catching the light and colors like butterflies in a net. The outside is inside: shadowy, silent, upside down.

It makes unfamiliar what has become only recently familiar. For you, who are new to this fancy high school (where you teach kids with more money than you knew existed in the world), to this Western landscape, to the dry creek beds and enormous boulders (you thought they were only a myth!), far from the Louisiana town where you spent the years since your early adolescence scratching at — punching fingers through — a limited, muddy, boulderless map, for you, in this room, this new place is doubly strange. It is dizzying, this disorientation.

So you push aside a bedsheet and step through a shaft of projected light that contains in its colors the orange of a school bus, the gray-brown of late summer grass, the fish-school shimmers of students dismissed. The photographer is leaning there, arms crossed like a museum guard.

You pester him with inane questions, growing bolder (boulder!) and clumsier by the minute. You ask how it works, the camera obscura. You ask him to show you his lens. You ask why the browning grass seems to sway so slowly, why the room feels so still, and you ask this unrelated thing that you’ve always wondered and been too embarrassed to ask — and he seems like the kind of man who would know, so here goes: How come we’re not upside down in mirrors? You ask this and begin to comprehend the physics of mirrors at the very moment the words are leaving your mouth, and by the time he blinks that slow, deliberate blink and embarks upon an epic explanation, through which words and logic are applied at last to intuition, you understand completely the principles of reflection.

You find yourself crowding him into a corner and cut short your questions to kiss the strange mouth that you can’t believe is the same mouth that smiles such a warm and charming smile (he does have a very nice smile, everyone agrees on that) but then snaps at a strawberry like a toad swallowing a moth, in three jerking, chomping bites. You remove the glasses from his eyes and say, in a voice like Ingrid Bergman — is it Ingrid Bergman? no, it’s someone irrelevant from some movie you hate, but you’re going to do it like Ingrid Bergman — so you say, Oh darling, you had me at angle of incidence.

*

Actually, you do not do — would not do — would you? — any of those last few things although you loll for an hour in bed one morning thinking them up while your husband clatters and clinks things in the kitchen and finally — how you wish he would stop, just stop — brings you coffee with a touch of cream, no sugar, just like you like it, and two pieces of toast, one buttered, one jammed, just like you like them. He is feeling good today.

In only a year, much has been revealed, including the presence in your husband’s liver of a virus, the treatment for which is more agonizing than the disease itself, which will eventually kill him, but not now, not soon, maybe not for many years — years and years! — so why must the treatment come now, in this fumbling first year of marriage, two-thousand miles from your selves as you knew them? The daily doses of poison leave him worn, desiccated and patchy-haired. Yet he is unaccountably cheery! It is his nature, as it is the duck’s to quack, the scorpion’s to sting. Why now?

It was your choice to come here, for a job that you were far more excited about than the last one, mostly for the reason that it was somewhere other than Louisiana. You were always a little strange there, terrible at the rollicking joie de vivre that your uncles and aunts and cousins performed so easily, the bullshitting, the weekends fishing and swilling beer at river-camps, the rapture with which they flung themselves — Tarzan-like on rope swings — into the water. And when you found a man (your now-husband) who was a little bit something else, but also a little bit the something you were, you hung on. He read a novel now and then. Harper’s. The New Yorker. Remembered, and cared about, everything he read. Why not marry this man? Where were you going, anyway?

But so much must be struggled through, a lifetime of struggling — how could you not have considered the outrageous length of the life before you? — with this man whom admittedly, admittedly, you love but (well, why not say it?) who came with an array of exasperating qualities that predated the discovery of the virus and have continued unabated even now, quite disproving the indelible virtue of the gravely ill. It’s the overdue credit cards and parking tickets, the exotic ingredients left to rot in the fridge or stale in the pantry, the expensive birthday-gift bicycle that was stolen before you even knew it was yours (he left it leaning, untethered, on the back porch all night), the time he forgot the window open and the cat fell three floors to the pavement and broke a leg. That the animal he would be if he were any animal — if he could choose to be any animal — is a duck. You married a duck, you think now. How could you have married a duck? And yet, you can’t bear to imagine forgetting these things. You can’t bear to think that one day, your memory of his face could be foggy and painless, that one day (not soon! not soon!) you may not be there to bicker with nurses, sleep in armchairs, and stroke the forehead of your ailing duck.

It’s other things too. It’s even the things you love (or once loved): all the reminders, great and small, that he comes from where you come from. His amused contempt for the singlewides you both grew up in. His mispronunciation of words and names he’s seen but never heard (DosteeYOOski, he says, BORgeez, Seven SAMyoureye). That neither of you had — or even yet has — a passport. Has ever even seen a real-live passport. Has ever been anywhere, really, before moving West: Florida, Texas. Did that even count? The ironic (it was ironic, was it not?) mullet-and-mustache he wore when he first found you, a Masters student alone in a Baton Rouge bar, besieged by an intensely cologned middle-aged contractor who had first admired your hairstyle and then, when you said no thanks, you just wanted to go back to your book (it was Slouching Towards Bethlehem), called you a cold-hearted cunt. Your would-be husband swooped in with his mullet-and-mustache, edged the contractor aside, said he’d just read an article in The New Yorker by Joan Didion, about Hemingway, whom he liked less than Didion herself. “‘Goodbye to All That,’ ” he said. “Have you gotten to that one yet?”

He worked in the sprinkler business, had no better than a GED, but he was a reader, he said, sort of an autodidact, and at the word autodidact, you swooned a little, didn’t you? At the mess of contradictions? Don’t you remember how you swooned? He had a truck and a GED and a Cajun name and a shelf full of Richard Brautigan. He knew where you were from, down to the very street, down to the very singlewide. My cousin lived in that park, he said. Do you know So-and-So? and you did, from the pool, from shimmying under the fence to catch frogs in the oxidation pond, from firing BB guns at the goats that kept the grass around the pond trimmed low. And you must have known him, too, then, one of the many sun-browned boys in swim trunks, on bikes and skateboards, rat tails at the base of their skulls, but neither of you remembered the other. Still, he knew where you were from and he knew what you were reading, and that was really something.

But here, away from his cousins and brothers and their boats, from the job where he’d risen to foreman, he is considerably diminished. He can’t find work, hasn’t much tried. He does not read anymore, has not bothered to put his own books on the shelves. In public, he defers to you, always. She’s the smarty, he says, cheerily, to your colleagues and new friends, with their PhDs and ABDs and allergies and locally roasted coffees. Talk to her. But more and more, under the cheer, he means it, and you can hear he means it, even if no one else can. Me, I’m just another coonass with webbed feet. All I do is quack. Quack quack!

You can’t say that here, you tell him. Especially in front of. Can’t say what where? he says.

Coonass. They’ll think you’re racist.

I can’t reappropriate my own ethnic slur?

They’ll think you’re talking about black people. Like, you know. You hesitate, of course. You know better than to say such words.

Coon? He says. That’s ignorant. It comes from French. Connasse. Do you know what that means?

You don’t. All you know are the squirmy glances exchanged among your colleagues.

Cunt, he says. It’s French for cunt. Go ahead and check the OED. Cunt.

Then, after letting that little gem hang in the air: The only brown people on the payroll at that school are the janitor and the Spanish teacher. Haven’t you noticed that? I don’t appreciate being policed by hypocrites.

Beyond all this, he is ill. This morning, after a period of grave dehydration and two days in the hospital hooked to pumps that filled him up again with fluids, he is almost wild with life. He wants to thank you, to do for you as you have done for him all these months, carrying him, carrying the insurance, really, that pays to treat an illness that is his own fault anyhow (but wasn’t that, too, one of the things you loved, still love? That he tried everything that could be tried? That he wasn’t afraid when his cousins passed him a needle and said, Try.) How reluctantly, how peevishly you’ve done for him he hasn’t noticed, or has refused to. You a damned good woman, chere, he says, putting it on like back home. Shoo, but I got me a good woman!

He brings you coffee and toast.

When later that same morning you bump into the photographer in the halls of the art annex where you’ve gone specifically to bump into him, you feel yourself turning quite red, and then — oh vampiric treachery (or, more concretely, your refusal to eat the lovingly toasted toast) — you feel yourself turning quite pale, and you know you are going to faint, and in fact, the floor and the ceiling change places and you come out of the faint with that face hanging upside-down over you. It’s truly a troubling face.

It’s the voice that’s most confusing. It lumbers out like a friendly bear from a cave and says, “Just lie still until you’re sure you can stand.” And though he’s still in that awful green shirt, he smells like sawdust and his hand is warm and enormous and sweeps the hair back from your forehead. The principal says to you, “Are you ill? Do you want a doctor?” and you say, “No doctor,” and the Latin teacher, the closest thing you have to a friend in this new place, squats down, leans in close to your ear and whispers, “Maybe you’re pregnant, mija.”

You can see that he’s heard this too, and there is an embarrassing, unspoken implication, though if pressed you couldn’t name it, and he blinks his eyes, but you fling out your arms in search of the tile, knocking away his hand, and finally you distinguish up from down and you’re standing and he’s still on the floor. Now, you snatch up your things. You bolt.

When you see him again at lunch, he says, “Have you recovered from your spell?” and you say, “I have,” and while you eat you find yourself leaning slightly in, slightly toward him, and you’re afraid your colleagues will notice the leaning, but lean you must, so lean you do. He crosses his legs and his rubber shoe rests lightly against your shin. You pretend to be the table.

For the next day, you celebrate, secretly. You feel you have passed a test, and you will allow yourself outrageous and wicked flights of fancy. You will pack up your things, move out on the husband, divorce, and marry immediately this brilliant, odd-looking man, and you will have brilliant, odd-looking children, and you will adore them all, and you will make them sometimes change their clothes. It will be saintly, how you adore them.

This almost, but not quite — not nearly — actually not at all assuages the guilt of even thinking of abandoning a man who will one day — not today, not tomorrow, not even soon! — be laid low by his own liver. It is amazing how often this slips your mind. You are appalled at the bifurcation of self that has allowed such thoughts. At the forgetfulness that, among other things, causes you in the middle of a grammar lesson, in front of fifteen mystified 15-year-olds, to laugh hysterically at the double entendre in a dangling (dangling!) modifier.

You concoct elaborate reasons to enter a room where he is, and once in that room, you panic and make abrupt, inexplicable exits. At school events you try to sit near him, not next to but directly behind, perhaps. At an assembly in the old Spanish mission that serves as a lecture hall and theatre, he is in front of you, just to the right, and about 15 minutes into the principal’s tirade against uncited or fallacious internet sources, against plagiarism, against cheating, you see him gazing at the ceiling, taking mental measurements of the room, of the windows, and he turns around and says softly, “I’m going to turn this place into a camera obscura.” You notice that he has changed his shirt.

For a week you see him crossing from studio to woodshop to lecture hall and back again with little wooden boxes and mirrors tucked under his arms. He boards up the windows in the lecture hall one by one. You run into him in the teacher’s lounge, and in a convulsion of glee he pulls from his wallet a mail-order invoice for two dozen lenses. He rattles it at you. “By the end of the week!” he says. Over lunch, he will speak of nothing but focal lengths and apertures. In that he is speaking at all, this is a vast improvement in his social behavior, but in another sense this development is, for your colleagues, excruciating. You listen, conspicuously and intensely. To everyone’s chagrin, you invite elaboration.

On Tuesday morning, between the usual announcements for quiz bowl practice and yearbook orders, he proclaims over the intercom the unveiling of the camera obscura. After the last bell, you come in with a group of other teachers, and you all take seats and drop your heads back to see the puddles of light on the ceiling above each window. One by one the others get up, say into the darkness This is amazing, good work there, buddy, and exit, and you finally realize that you and he are alone in the camera obscura.

He emerges from the shadows near you and says, “I’ve found that the best way to experience this is to lie down.” And you both lie down in the aisles and watch the clouds move across the ceiling, the leaves flutter slowly in the trees, no accompaniment to this movement but the creaking of floorboards under your back, the rush of your breath, and the electric crackle (are you imagining this?) between your feet and his, no, that’s the click and hiss of an IV drip in the stillness of a hospital room, like the steady click and hiss of a camera on time-lapse, or actually it is his camera on time-lapse and it’s recording the reflected movement of clouds. On the ceiling just above you is the main road and the gas station across from the school, its empty parking lot, utter stillness, and when a blurred human form exits the gas station and moves away, toward the frayed edges of projected light, and then disappears into shadow, it’s like discovering a code in the static of space. It is frightening and ominous and sad, it is a glimpse of the future of a memory.

You think: We are watching forgetting. This is what forgetting looks like.

You take a breath and say this, and there is no answer.

Half an hour passes and the two of you manage this much more conversation:

“Is it Tuesday?”

“Yes, it is Tuesday.”

Finally, with nothing else to say, you pick yourself up from the floor, dust yourself off. You’re right in front of the lens box, your head is blocking the sun — you can feel the hot coin of it on the back of your skull — and you idiotically make hand shadows of an octopus swimming across the sky. There is no response. As you shuffle up the aisle, he says from the darkness, “Thanks for coming. Come back!” and you wonder if he means right now, tomorrow or nothing at all.

One buoyant blue morning you are inexplicably crackling like cellophane, trembling with agape. This morning, this joy is a balloon that you tap with the tips of your fingers, a slow volley to the janitor, and he taps it back to you, and to the principal, and he taps it back to you, and to the Latin teacher (who is now absolutely certain that you are “expecting,” and you are, but what? what are you expecting?) — tap! with a flourish of wriggling fingers — and each of them smiles a true smile, a this-morning-in-June smile (although it is, of course, not June but nearly November).

It’s the weather. It’s only the effect of the weather. Such interminably, oppressively beautiful weather.

It compels you to ask the photographer if he would like, after school, to go for a hike. When you call your husband, you don’t even bother to lie. He has seen the photographer (granted, from a distance, when picking you up from school), and you have composed a careful portrait besides — the rubber shoes, the off-kilter remarks. This could not be more than simply a hike.

“Sure, okay,” your husband says. “I can’t do that with you right now. I want you to have someone to do that with.”

He has a cowboy-ish walk, very straight, and he strolls over boulders with no change in his posture, never bending, never grappling for a foothold, not at all like the scrambling squirrel you are. You trip over rocks, fall on your ass not once but twice. “We don’t have rocks where I come from,” you say, and he laughs, but it isn’t really a joke. You and he climb up and up, up and up. Finally, you reach the top, the end, the vista, and there at the vista, there is a bench, only feet from a fierce drop-off.

You both sit on the bench with a little space between you. You hear him swallowing. A tumble of frivolous questions presses, but you wait. Your teeth are chattering, you are shivering, although it is easily seventy degrees. You pretend to enjoy the beautiful view.

“So,” he says. “You moved here from the South. Where, again?”

“Louisiana.”

“You don’t have an accent.”

“No,” you say. “I got rid of it. Like Hilda Doolittle.”

“Eliza,” he says flatly. “Hilda is the poet. Eliza is the fair lady.”

“Right. Whoops.” Then, for no good reason, you say it again: “Whoops.”

“I’ve never been there,” he says. “Is it nice?”

You laugh. “Have you even heard of the South?” You crack a joke about racists and mullets and singlewides and meth-addict cousins in prison and when he only blinks at you, you think, okay, maybe I ought to be done making these jokes.

“You must be homesick,” he says, without sarcasm.

“Never,” you say. “Look at all this.” You sweep a hand at the vista. You are so far from everywhere. How did you get here?

“It must be nice to be from some place. My parents moved around a lot,” he says.

“Military?”

“Hippies.” He laughs but only in his chest and weirdly without moving his face. “They had a good time, but it was hard on me.”

You look at each other, at the same time, for the first time. He blinks and you blink. There is something yet that needs to be said.

He says, “Aren’t you — ?”

When the word “married” bobs to the surface like a drowned corpse, you feel like the world is upended and you will be shaken off. It’s gone over the cliff, whatever it was that sat between you, you kicked it over the cliff and you can hear it whistling all the way down until it hits the bottom in a little puff of dust. You begin the funereal march back down the trail.

There is silence for the first fifteen minutes of the journey, and you wonder through this silence if there is something required of you, an apology, an abandonment of ethics, but then, suddenly, he is merciful. He breaks into song, a sea shanty. O the year was 1778 — how I wish I was in Sherbrooke now! You think at some point he’ll surely stop, but he does not stop. He knows every verse, sings the whole thing — it goes on and on — in a robust monotone all the way back down to the trail head. Throws back his head for the final refrain and shouts it at the treetops: Goddamn them all!

You are in a state of vapid waiting. Your skull is a lean-to and you’re camped out under it, waiting for a change in weather. There is no change in weather. You start to blurt cryptic things to the colleagues, to the husband. Things like: My skull is a lean-to and I’m camping out under it. You feel you are speaking in rebus. You have trouble stepping outside the situation enough to determine exactly what is a problem, and exactly how much of a problem the problem is. You begin to suspect the problem is probably you.

At home, your husband resorts to antics. He requires your attention. (Of course he does. Of course he requires your attention.) He begins with little gestures, like startling kisses on the neck while you stand petrified before an open cabinet in your kitchen, arrested by despair in mid-reach for a coffee cup. Or he grabs you in a hug, pins your arms to your body, tweaks your breasts. It’s playful but angry too. Finally, he throws up his hands and says, “I just don’t understand.”

“What?” you say.

His eyes are bloodshot. He looks dry again. His fingers.

His ears.

“The sad,” he says. “You got what you want. We came all this way. I just don’t understand the fucking sad.”

*

You decide to come clean. You will take your chances with your one friend, the Latin teacher. A unicorn, she appears only to virgins, the pure of heart. Her eyes are wide and dewy, her gait is graceful, rolling — where her hips go, the rest of her follows. She told you once that she has exceptional — even mystical — powers of empathy, and you, earthbound flesh, believed her. You are beginning to know better, but all the same, she is a friend, your only friend, and the least discreet in her eye-rolling at your husband’s many social faux pas, so you confide everything — the virus, the camera obscura — but when you do, she cringes, as if you have raised your hand to strike her, and you think, my God, is it so awful, my God, is this my nature? She says, “Why are you telling me this? Your husband is sick. Why are you doing this?”

“But I didn’t,” you say, “I didn’t do anything,” and for the first time, it occurs to you this might be true.

As for the unicorn, she will appear to you no more. But screw the unicorns, you think, let’s be more objective. The fact is, before all this, before the obligating virus, you had been thinking that you’d better just pick someone to love already and be done with it. Love, you told yourself, after two critical, devastating failures, is a choice and not a visitation, is not the shared transport of a 4:00 a.m. binge on Borges and a can of sardines, is not transcendence or revelation, has no empirical epistemology. It is like-mindedness on questions of dinner and dishes and laundry. It is, you have learned now, tolerance of peculiar sounds from the bathroom, the daily jamming of needles into thighs. You pick someone, that’s all. You pick someone who knows where you are from and dig in. Ritual evokes reverence; every injection, every slice of buttered toast conjures affection. Was this cynicism or was it faith?

At home, your husband has excused himself from living. Your health insurance is the only thing between him and — what, exactly? This is also unclear. He plays video games. He has drawn the living room curtains and sits cross-legged on the floor, his hands working the controller, in darkness except for the glow of the television, and surrounded by plates of shriveled pizza, crumpled taco wrappers, empty or half-full bottles of sports drink, all toppled and scattered. He spends an hour (an hour!) on the phone every day with his brother. When you ask him how he is feeling, he says, cheerily, “Fine, fine! And how are you doing?” then goes back to his game, his phone call. You might as well be greeting each other over cantaloupes at the supermarket.

Then, one evening, in who knows what season, after who knows how long, you find him there on the floor and say, “Why don’t you just go home? I’ll buy the ticket. Please just go home!”

“Don’t yell at me,” he says. “Goddamn,” he says.

“Fuck this,” he says. “I thought if we left you’d be different.”

As one does in times of trial, when the truth is clear except to the self, you have a dream. In your dream, your husband is a plate of sushi. He is laid out in fleshy pinks and whites upon a bed of rice and wrapped up neatly in cellophane. You peel back the cellophane — a naked, private, alarming sound — and pat the shrimp. “I’m sorry,” you say. “I’m sorry this is so hard.”

At school, the photographer doesn’t blink at you anymore, and in fact each of you pointedly ignores the other, but sometimes you still manage intentionally accidental contact. One day, you have somehow both landed on a park bench in the courtyard outside the annex. He is, incongruently, the sponsor of the school yearbook, and three art girls dash over and flutter around him, they want the key to the darkroom, and they cram themselves onto the bench, shoving the two of you together. They tug and nip at him like puppies at an old hound dog. “Oh, Mr. So-and-So, you know you can trust us!” There is gray at his temples, and — you see that you were wrong, he is actually quite handsome. How could you have been so wrong? He produces the key and the art girls dash away again, leaving you thigh to thigh on the bench.

You say — you try to say — what can you say? You say nothing.

He says nothing.

Neither of you says anything.

When the fifth period bell goes off, you rise together, and in the confusion of walking away, out of a habit that was never actual but only imagined, you grab hands, you enfold fingers, you squeeze.

This startles both of you. It will never happen again.

__________________________________

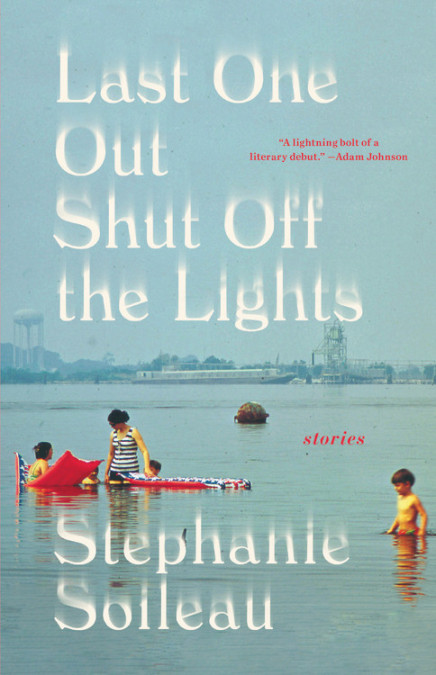

Excerpted from Last One Out Shut Off the Lights. Copyright © 2020. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.