“Whoever loves passionately / and keeps that love chaste / and hides it / and dies in that love / has died the death of a martyr.” — Hadith (Suwayd ibn Sa`id), translated by Omid Safi

I’ll never understand completionist critics. It’s better, they would have it, to see 10 unique films than only eight unique films with two re-watches littered in the mix. There are so many movies that it would be a waste to spend your precious waking minutes revisiting old film friends. In the most extreme and (in)famous example, the New Yorker’s long-time critic Pauline Kael vehemently refused to ever revisit any film. Even for a canonical picture like Battleship Potemkin (1925) or something more indisputably complex like Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (1977), Kael, supposing she was honest, would have resisted any temptations to re-evaluate. Once was enough.

Once is not enough for In the Mood for Love.

In 2012, Wong Kar-wai’s consensus masterpiece was named the 24th greatest film of all time by Sight and Sound’s decennial poll. The same film polled at #5 in 2022. The incredible rise up the most acclaimed and accredited industry poll can be explained in part by the diversification of those being polled—and also, in part, by critical revisitation. As the South China Morning Post argues, the original response to the film was “initially muted” and received extremely limited coverage, if one can even call it that, from several major outlets like The Guardian. The industrywide re-evaluation can’t simply be explained through first-time watches from established critics; something more must be at play. Rapid canonization of this scale requires rewatches and reevaluations on an individual level.

And while I am a far way from voting in the Sight and Sound poll, my own history with the film attests to its rewatchability. My first time with In the Mood for Love came early in my Wong phase, and while it wasn’t a complete miss, it felt like a step in a downward trajectory following Chungking Express (1994), an immediate personal favorite. There was just something missing—whether that was in me or in the film, I’m unsure. My fondness grows with every return, and it’s slowly becoming one of my favorites of Wong’s—even if it’s a bit atypical for him in several key ways.

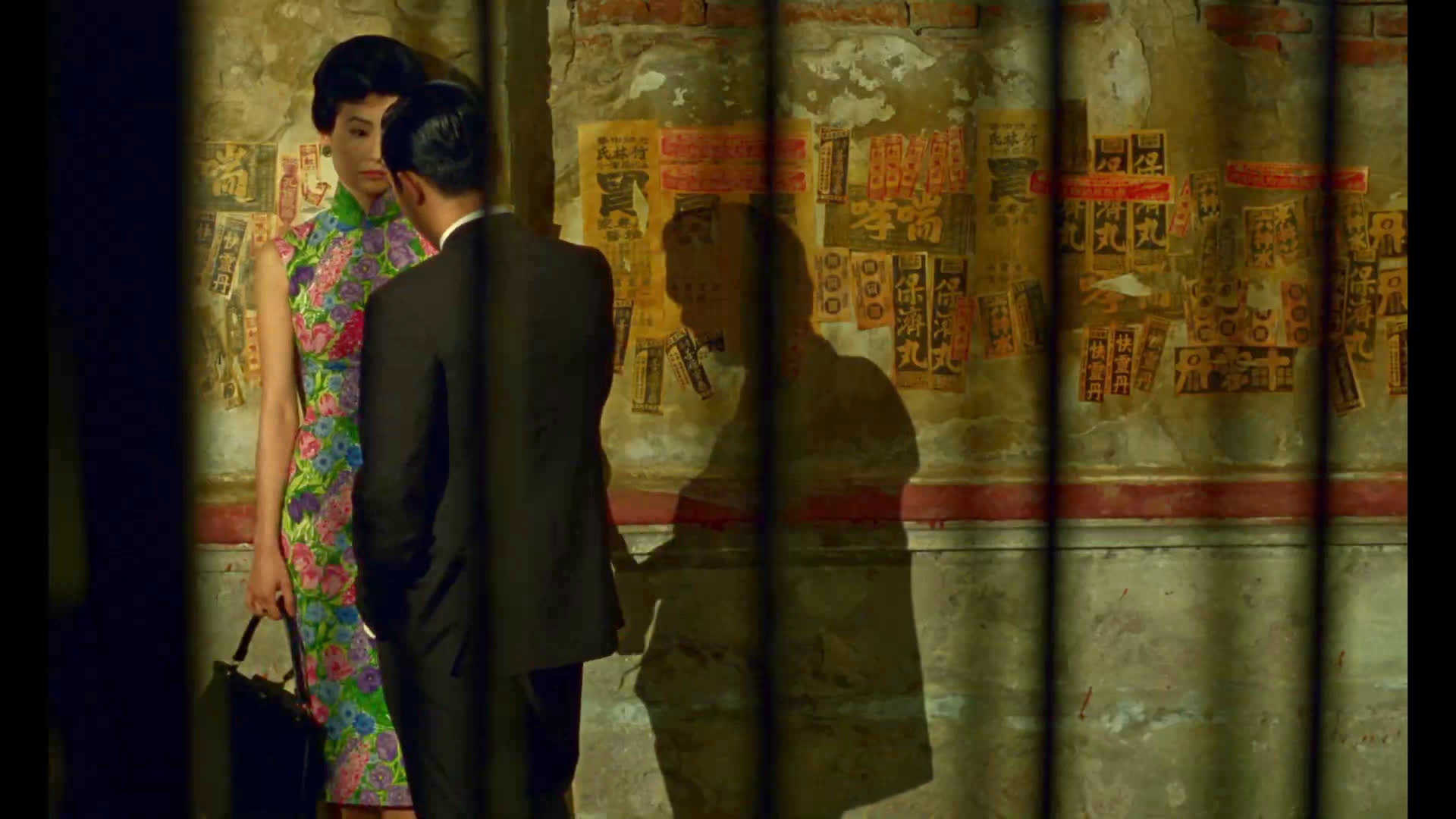

Two couples, the Chans and the Chows, move into an apartment building on the same day in 1962 British Hong Kong. Once Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) and Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) piece together that their spouses (whose faces are never seen on camera) are having an affair, the two “victims” role-play the affair with each other and eventually develop (chaste) feelings of their own. The simple story is complicated, at least for uninitiated viewers, with unconventional editing that chooses not to abide by the traditional rules of space-time. A meal at one time suddenly cuts to a meal at a later time in the same space, or a character entering a hallway at one moment reappears not at the next moment but in the same geographical space a week, or perhaps a month, later. The spaces and those who occupy them become divorced from time. The unseen spouses’ long nights away from their marital beds are never-ending and they never fully return home. Unified tones and experiential truths, rather than the “correct” sequential combination of space and time, make the scenes comprehensible.

The editing, aided by Wong’s step-printed trademark look, reminds me of one of the great passages in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s renowned magical realist novel. In the selection, a soldier son is killed in battle and his blood weaves, trickles, and maneuvers its way to the dead soldier’s mother:

“A trickle of blood came out under the door, crossed the living room, went out into the street, continued on in a straight line across the uneven terraces, went down steps and climbed over curbs, passed along the Street of the Turks, … went along the porch with the begonias, and passed without being seen under Amaranta’s chair as she gave an arithmetic lesson to Aureliano José, and went through the pantry and came out in the kitchen, where Ursula was getting ready to crack thirty-six eggs to make bread.”

The sentence, which I have abbreviated here, bypasses traditional grammatical conventions of sentence and noun phrase lengths, as well as realistic ideas about the physics of blood, to artistically illustrate the deeper relationship between the grieving mother and her now deceased son. The truth behind the relationship outweighed the usual limitations of grammar and spatial realism. In the same way, Wong’s powerful storytelling devices, including but not limited to editing, bypass the need for such petty limitations and elevate its deeper truths—truths that, as the film’s final shots attest to, prove political and even national. As in Marquez’s great novel, the heterodox style collapses time on itself—prolonging the marital collapses of the two couples and expanding the potential for a union between Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow.

The final shots of the film have also grown on me. In what first appears to be an alien political shift, Mr. Chow visits Angkor Wat following newsreel footage of Charles de Gaulle’s visit to Cambodia in September 1966. The reason for the abrupt trip is little more than an excuse for abruptness itself. According to Wong, “We wanted an ending ‘with a distance,’ the two characters distanced from their usual surroundings. And the newsreel about De Gaulle arriving in Cambodia…more than the historical event itself, I liked the idea of showing another kind of waiting, the people of Cambodia waiting for something on the streets.” He added on a later date in a Chinese language online film discussion, “The ruins also reflect a glorious time that cannot be returned. In the movie, the two main characters find difficult to evade from each other, but there are no secrets and memories to return to.” What once felt cold in its abruptness, upon a revisit, now feels to me more like one last whisper to a forbidden lover.

I’m reminded, in these final moments, of a lesser-known hadith (a transmitted report of what the Prophet Muhammad said during his life):

“Whoever loves passionately / and keeps that love chaste / and hides it / and dies in that love / has died the death of a martyr.” — translated by Omid Safi

Mrs. Chan, and especially Mr. Chow, are cinema’s greatest martyrs of love. A sexually charged and forbidden chastity, the couple deny their own pursuit of happiness for the sake of other responsibilities, for other commitments, for an unwillingness to turn the metaphorical gun once aimed at them back to their own spouses.

With Brattle Theatre’s upcoming 35mm showings on the 26th, it’s the perfect chance to revisit the film under ideal conditions…and with a bonus opportunity for a back-to-back viewing with Everything Everywhere All At Once. Or, even better, see it for the first time!

In the Mood for Love

2000

dir. Wong Kar-wai

99 min.

Playing on 35mm at Brattle Theatre on Dec. 26 at 4:00 and 6:15pm.

Double feature w/ Everything Everywhere All at Once

The post GO TO: In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai appeared first on BOSTON HASSLE.